Queer Modernisms

This exhibit was created from a series of tagged objects on the original ModNets interface. It is unclear who originally collected these items, and the items are compiled here as a means of preserving the work of this unknown individual or individuals.

The exhibit has been compiled into its current form by Dr. Lauren Liebe and is meant to serve as an example of the functionality of the new exhibit builder.

Table of Contents

Introduction

This collection of resources is built out of objects tagged as “queer” on the original ModNets site. The tagging system has now been retired in favor of a more expansive exhibit builder that allows users to collect and comment on their material. However, in the interest of preserving content previously available, we have reconstructed this collection here, with some light commentary as to the nature of the items in the collection.

It is unclear exactly what the criteria for tagging items in this collection was. While the tags encompass most of the materials that would have been returned for a search of the keyword “queer,” some curation does seem to have been performed. This collection may, then, reflect an incomplete research process which highlights a overlap between the previous tagging and collection systems.

If you are the originator of these tags (or if you would like to help us expand this exhibit), please contact us!

Journals and Magazines: The Modernist Journals Project and the Blue Mountain Project

The word “queer” appears in many contexts throughout many of the modernist journals and magazines collected in the Modernist Journals Project and the Blue Mountain Project.

- The Seven Arts (1916-1917): Includes Sherwood Anderson’s short story “Queer.”

- The Glebe (February 1914): Includes R. A.’s poem “Vates, the Social Reformer.”

- Bruno’s Weekly (22 January 1916): Includes Tom Sleeper’s poem

Resources from Woolf Online make up the bulk of the items collected under this tag.

- Page 112: “She had for it some irrational tenderness; it gave her, as it gave her children, some queer ecstasy;

some?&the sight ofthatthose lights, the two quick lights & then the long light…” - Page 171: “It has

suddenlybecome unreal, thought Lily Briscoe, trying to account for the feeling of exhileration which had taken possesion of them; & thinking how it waspartlylike the scene on the tennis lawnoveragain,& waswhen they were all so light hearted, & was partly due to thequeer lighting– these little candles in the large, sparely furnished room, & the uncurtained windows…” - Page 172: “…room, in a queer half dazed, half desperate way, ‘What does one send to the Lighthouse?’ as if she were forcing herself to do what she despaired of ever being able to do.

What does one send to the Lighthouse indeed! At any other time Lily could have suggested reasonably tea, tobacco, newspapers. But this morning everything seemed so extraordinarily queer that a question like Nancy’s — What does one send to the Lighthouse? — opened doors in one’s mind that went banging and swinging to and fro and made one keep asking, in a stupefied gape, What does one send? What does one do? Why is one sitting here after all?” - Page 220: “Now Nancy burst in, and asked, looking round the room in a queer half dazed, half desperate way, ‘What does one send to the Lighthouse?’ as if she were forcing herself to do what she despaired of ever being able to do.

What does one send to the Lighthouse indeed! At any other time Lily could have suggested reasonably tea, tobacco, newspapers. But this morning everything seemed so extraordinarily queer that a question like Nancy’s—What does one send to the Lighhouse?—opened doors in one’s mind that went banging and swinging to and fro and made one keep asking, in a stupefied gape, What does one send? What does one do? Why is one sitting here, after all?” - Page 222: This page is a third iteration of the passage on page 172 and 220, with some edits, though the content of the passage remains largely the same.

- Page 224: “

& wished to survive, surely

she survived & wished to surviveYet from the flash of her sidelong glance, its queerness, & why she seems& her lurch & her smile”

This section shows a great deal of editing, with much of the text being marked for deletion.

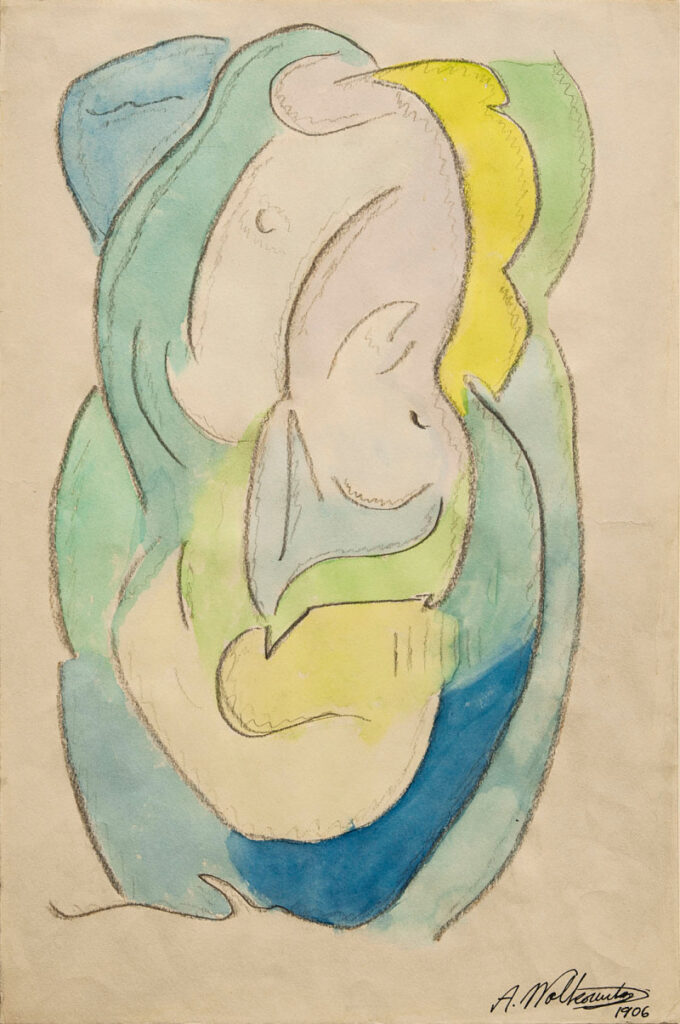

The Note Books of a Woman Alone

The Note Books of a Woman Alone is a digital critical edition of the book of the same name, originally published in 1935, edited by Mary Geraldine Ostle. The Note Books were initially derived from notebooks written by an unknown woman given the pseudonym Evelyn Wilson by Ostle. The introduction to the critical edition highlights Wilson’s alienation from the society around her, in part because of her unmarried status. In a social milieu in which “the centrality of sexual desire in psychic life meant that spinsters could readily be maligned as neurotic, morbid, deviant, and even predatory,” XA Wilson’s writings may thus prove fruitful for queer readings.

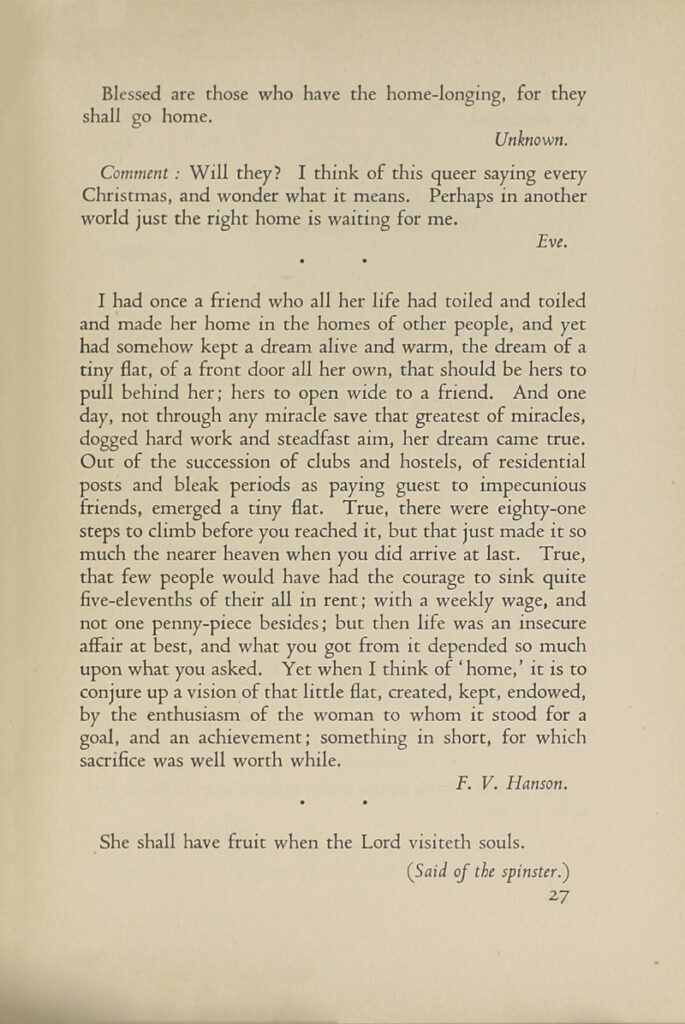

Two items have been tagged from this archive: page 27 and page 76.

Page 27

The relevant section here includes a quotation followed by commentary from Wilson.

The anonymous quotation reads “Blessed are those who have the home-longing, for they shall go home.”

Wilson asks, “Will they? I think of this queer saying every Christmas, and wonder what it means. Perhaps in another world just the right home is waiting for me.”

This item may simply have been chosen because it includes the word “queer” in its text. However, it is also a particularly poignant example of the extreme solitude reflected throughout the Note Books.

The relevant passage on this page reads “Such invariable and unwearied courtesy is in an especial sense due from us to all servants, and to all queer, retiring, nervous, and unsuccessful people.”

Again, the page appears to have been tagged due to the appearance of the word “queer,” and, again, this passage associates queerness with a keen sense of loneliness.

Page 76

Works Cited

XA: Ophir, Ella. “Introduction.” Ella Ophir and Jade McDougall, editors. The Note Books of a Woman Alone: A Critical Edition of the 1935 Text. University of Saskatchewan, 2016, drc.usask.ca/projects/notebooks/introduction.php.

This section cites Allison Oram’s Women Teachers and Feminist Politics, 1900-1939. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1996.

You can also add a suggested citation, Creative Commons licensing, or other information about how to use and share this exhibit.